Coaching skills are highly transferrable and exceedingly valuable. And they are also very trainable.

With conscious effort, anyone can enhance their ability to communicate better, listen more attentively, or motivate others to grow – whether that’s as an individual or as an employee.

But what skills should we focus our efforts on, to become a better coach? And which techniques are best for different contexts? In this article, we’ll cover some essential coaching skills that are worth developing and how you can train to become a more effective, more powerful coach.

Essential Coaching Skills to Train

The International Coaching Federation (ICF) is perhaps the most well-known credentialing body for aspiring life coaches, and it defines coaching as (ICF.com, 2019):

…partnering with clients in a thought-provoking and creative process that inspires them to maximize their personal and professional potential.

ICF credential-holders do at least 60 hours of applied training to gain the minimum ACC (Associate Certified Coach) certification and commit to excellence and continued development as laid out in a professional code of ethics. So what are the ICF ‘Core Competencies,’ or essential coaching skills, that they test for?

There are 11 in total, which fall into four broader categories.

1. Professional Foundations

This involves a coach’s ability to meet professional standards, ethical guidelines, and establish a coaching agreement. While different bodies have varied ethical guidelines, every coach should be able to understand and apply the relevant standards in their practice.

They should be able to start from a clear place where their clients know what they are in for, and in particular, the difference between coaching and therapy, mentoring, and similar. As well as clarifying what coaching entails, practitioners should be able to define some clear parameters for their continued relationship – including ‘practical’ issues such as fees and timeline.

2. Relationship Co-creation

All coaches should be able to develop trust and professional closeness with their clients, which creates a psychologically safe climate for their ongoing work together. It includes providing support, respecting boundaries, commitments, and being genuinely concerned for their well-being.

The ability to maintain good coaching presence is another skill the ICF considers essential, and it entails being present, appropriately sensitive, and self-management, among other things.

3. Effective Communication

It may seem fairly obvious, but with good communication skills, a coach can make the entire experience much more effective in terms of results and the working interpersonal relationship.

More specifically, coaches with solid communication skills can gather relevant information, identify their client’s motivation and morale, provide feedback, and establish rapport (Stone, 1999). There are myriad ways to improve your communication skills, but the ICF highlights three in particular:

- Active Listening – by listening attentively, with the coachee’s interests in mind, and exploring issues further;

- Powerful Questioning – to identify not just facts, but possibilities (Kroth, 2007); and

- Direct Communication – including, but not limited to, conveying understandable information, reframing where required, and using appropriate terminology.

4. Promoting Learning and Outcomes

To move toward results, coaches often need to shift a client’s perspectives or help them reach new understandings. Usually, this involves creating awareness in the coachee around circumstances, emotions, and perspectives, for instance, where a client’s perceived barriers are not grounded in reality. A coach can then help plan goals and design actions that will take the client toward their desired outcome.

Last, but not least, the ability to manage progress is an essential coaching skill which allows practitioners to follow up on their client’s commitments while placing the responsibility for those actions firmly with them.

What Techniques Does An Expert Life Coach Use?

The competencies we just looked at are by no means definitive, nor are they the only essential skills that a coach will find useful in his or her career.

The concept of ‘essential’ skills is an interesting point of contention in the literature. It’s worth noting that to date, no empirical research has examined which skills impact coaching effectiveness (Kampa & White, 2002), nor is there seemingly “a universal credential…to identify competent coaches’’ (Joo, 2005: 476).

On top of these arguments is the fact that the life coaching industry remains very much unregulated, so there are no exhaustive or conclusive lists of skills to refer to.

Throughout this article, we’ll consider some useful techniques commonly linked with the above list of skills. These include communication Techniques such as open-ended questions and feedback delivery and motivational Techniques like visioning, self-esteem building, and various approaches to goal-design.

What Other Techniques do Coaches Use?

Elsewhere in our articles, we’ve also looked at the overlap between positive psychology and life coaching. This is readily apparent in the fact that lots of life coaches also choose to use positive psychology interventions such as:

- Imagery and visioning motivational techniques (Gilley & Gilley, 2007) – Such as guided imagery, goal visualization, and guided meditations. These are often a positive and highly powerful way of clarifying intention and promoting goal-directed behavior;

- Mindfulness exercises – These can include imagery exercises, but also help clients to focus their attention and deal with everyday challenges (Collard & Walsh, 2008). They may sometimes be part of their action plans, depending on their individual goal; and

- Gratitude exercises and activities – Where clients find that negative thought patterns are obstacles that they want to overcome, techniques such as gratitude journaling, letters, and lists can be useful.

Let’s start with a look at the communication techniques that coaches rely on.

Tips for Coaching: Communication Skills

Whether it’s gathering information, delivering feedback, or building trust, coaching relies heavily on healthy two-way communication. As well as active listening, which we’ve touched on above, life coaches may use:

- Techniques for effective feedback. There is a very broad consensus among experts that effective feedback is as timely as possible – if not immediate. Research shows that it is also gentle but specific, clear, delivered with the client’s desired outcome in mind, and delivered in a way that encourages them to self-reflect (Losch et al., 2016). Depending on the individual life coach, this could involve ‘Chronological fashion’ feedback, the Pendleton Model, or any number of informal acronyms (Hardavella et al., 2017);

- Open-ended questions. A crucial part of listening actively, open-ended questions encourage clients to develop greater awareness around their perceived challenges (Dembkowski & Eldridge, 2003). In comparison, closed questions invite short, direct answers – precluding any additional insight into a client’s way of thinking, motives, and perspectives;

- Nonverbal techniques. Emotional intelligence skills play a massive role in coaching, and non-verbal communication is critical in healthy coach-client relationships. Expert life coaches are keenly aware of how to use body language, eye contact, and tone of voice to make their clients feel as supported and psychologically safe as possible (Kroth, 2007). This encourages sharing, openness, and can boost a client’s motivation.

Expert coaches don’t limit themselves to these techniques, by any means – the above are just a few examples. It’s probably far more accurate, concise, and helpful to think of effective communication differently entirely. In other words:

Effective coaches make a conscious effort to be aware of their communication styles and pay attention to their clients’ communication tendencies in turn. They can thus switch effectively between different techniques, based on what will be most effective for their desired goal.

Leary’s Rose (1957) is just one highly useful example framework that coaches can look into for a whole diverse range of communication styles.

Motivational Techniques

So, how does a great coach keep their client motivated? There are numerous ways to keep clients driven and sustain momentum: effective goal-setting, giving the necessary support, and helping them overcome obstacles along the way.

1. Effective Goal-Setting

Helping clients design appropriate goals is a critical motivational technique in itself. In life coaching, especially, goal design involves tapping into the personal values that your client holds dear and transforming those into concrete, clear commitments. To assess your client’s values, please see this post.

Techniques include (Locke & Latham, 2002; 2006):

- Ensuring goals are appropriately challenging – overly-simple goals are dull, while excessively difficult goals are overwhelming;

- Making them explicit and actionable;

- Building in rewards and feedback to sustain momentum;

- Breaking them down into sub-goals and charting a pathway for success;

- Creating positive, approach-focused goals (rather than avoidance-based goals) that emphasize achievement and success; and

- Collaborating to brainstorm pathways and alternatives.

2. Providing Feedback and Support

We can even take some tips from sports coaches, who are the most powerful source of performance feedback for driving athletes’ performance. The support they provide is critical in helping athletes build up their self-efficacy, sense of competence, and thus, their self-esteem (Sullivan & Strode, 2010).

Research shows that perceived competence, ability, and enjoyment were found in athletes whose coaches provided higher frequencies of informational feedback to their athletes, as well as greater intention to continue playing (Sullivan & Strode, 2010).

Off the field and in the office, executive coaches who provided more feedback (described as coaching intensity) were associated with employees who demonstrated good sales performance (Agarwal et al., 2009). In contrast to a command-and-control style of coaching, this feedback-rich developmental approach was much more motivating.

To keep clients motivated, evidence suggests that coaches can thus provide constructive, informational, and performance-related feedback as much as possible.

3. Encouraging a Positive, Growth Mindset

Coaches themselves can bring a positive mindset to their interactions to foster the same in clients (Dweck, 2009). By supporting a growth mindset in clients, they can enhance their motivation to improve and develop their capabilities. When clients are focused on learning, when passion and dedication drive effort, they are better able to overcome obstacles along the way.

A supportive coach who encourages clients to develop a growth mindset can help them accept their shortcomings and any mistakes they make on their journey, boosting their self-confidence and pushing them to implement their intentions for improvement (Driver, 2011).

4. Developing Resilience

Adversity and setbacks are part of life – they are frequently a part of an individual’s coaching journey. Resilience is the ability to be flexible and adapt when challenges arise, helping them back on track when they are knocked off course (Luthar et al., 2000).

Coaches who can help their clients develop resilience will not only encourage them to persevere but can help encourage greater well-being (Carrington, 2013). Specifically, coaches can:

- Help clients use critical thinking and identify perceived obstacles to goal achievement;

- Provide alternative perspectives to challenge any ‘thinking traps’ which are solely mental;

- Assist them in learning from past mistakes, providing tactics and strategies for the way forward;

- Help construct realistic, practical plans for the client to pursue themselves.

Effective Coaching Skills for Leaders and Managers

As increasingly more firms look to develop skills from within, coaching has almost become a pro forma leadership skill. Leaders who encourage others to ‘own’ their professional development are essential in any future-focused organization – they can foster engagement, stimulate better performance, and drive others toward personal and professional success.

In a lot of ways, leaders and managers rely on the same core coaching skills as life coaches. Nonetheless, they differ fundamentally: at its very core, workplace coaching is about enhancing individual performance for the organization’s strategic benefit (Jones et al., 2015).

So, while workplace coaching outcomes professionally benefit – and are valued by – the individual coachee, they have two mutually inclusive purposes (Smither, 2011).

1. Aligning Organizational and Individual Goals

Thus, business coaching relies on the successful alignment of individual and organizational goals. The mini-table below gives just a couple of examples of how business coaching goals are always designed to be mutually beneficial for the employee and the organization:

| Example Benefits | ||

|---|---|---|

| Example Coaching Goal | For The Employee | For The Organization |

| Develop Leadership Skills | Enhanced internal promotion opportunities; Greater sense of purpose “I’m going somewhere vs. another day, another dollar” |

Succession planning; More multi-skilled workforce; and Greater organizational adaptability. |

| Improve communication skills | Highly transferrable skill set to other life domains; Less frequent misunderstandings – including duplication of effort and stress; and Improved self-expression. |

More efficient cross-functional collaboration; Fewer potential conflicts; and Higher productivity. |

Sources: Kellogg Insight (2017); Amabile (1993).

This creates a need for leaders and managers to develop skills that can support this “balancing act,” for example:

- Self-awareness – Recognizing when to switch between managerial/leadership and coaching “hats” (Brocato et al., 2003);

- Adapting their approach accordingly – in other words, general and psychological flexibility (Yukl & Mahsud, 2010); and

- Situational awareness – which comes hand-in-hand with self-awareness, helping leaders decide when and how to coach others.

In a nutshell, most of these skills can be linked back to emotional intelligence, which research has linked consistently to coaching leaders (David, 2005; Grant, 2007).

2. Balancing Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation

It probably sounds ridiculous when written so plainly, but life coaches don’t reward their clients to reinforce desired behaviors. They consider only the client, and they will usually encourage them to engage in self-motivating behaviors, but at the end of the day, life coaches don’t need to worry about an organization’s strategic goals.

Employee development or workplace coaching, however, takes place within the much broader, interconnected context of the whole firm.

So, coaching leaders need to consider how their practices will link to existing extrinsic reward systems in place – pay, time to pursue personal projects, flexible working arrangements, and so forth, aiming for a balance that suits everyone. This balancing act is a skillset in itself.

For a better understanding of what it entails, we can look at Harvard Professor Teresa Amabile’s 1993 paper entitled Motivational Synergy, which suggests that leaders need to be able to:

- Understand individual worker’s motivational orientations – some staff may be more driven by growth opportunities, some by autonomy (Hackman & Oldham, 1976; Deci & Ryan, 1985);

- Offer work experiences that increase individuals’ skill flexibility, sense of competence, and employability (strong intrinsic motivators); and

- Use “synergistic motivators.” These are external rewards that support intrinsic motivation ‘synergistically’ – they support our sense of competence (intrinsic motivation) without undermining our sense of self-determination. We dive into these here, and I recommend the above paper if you’re curious.

A Side Note: Leaders as Coaches

For those interested in learning more about the benefits of employee coaching, the Ability, Motivation, and Opportunity (AMO) Framework very beautifully places workplace coaching into a motivational context. Just briefly, the AMO Framework premises that an employee’s job performance is heavily impacted by three things (Bailey, 1993; Edmonson, 1999; Appelbaum et al., 2000; Boxall & Purcell, 2003):

- Their ability to perform at a high level;

- The drive they have to do so; and

- Opportunity – for example, a supportive or psychologically safe environment in which to perform at their best.

Coaching helps workers set goals related to improving their abilities, and an effective leader or manager will help motivate them on the development journey. When an organization allocates resources to coaching, they are allowing staff to pursue personal growth in a way that is also professionally relevant.

4 Different Coaching Models

Whether you’re a life coach or an organizational leader, a framework can help you maintain a solution-focused outcome and navigate the journey ahead with some structure. Because there are vast numbers of different models in practice, we can think about them as falling into at least a few main categories (Stout-Rostron, 2009; 2018):

- Quadrant Models – including GROW and Kolb’s (1984) Experiential Learning Model;

- Circular Models – such as the ITO (Input, Throughput, Output) model;

- Nested Models – for example, Weiss and colleagues’ (2004) original 3-level model and its variants; and

- The U-Process Model – referring to one specific change and learning framework by Scharmer (Scharmer et al., 2005).

Here are four of the most common models you’ll find life and professional coaches using.

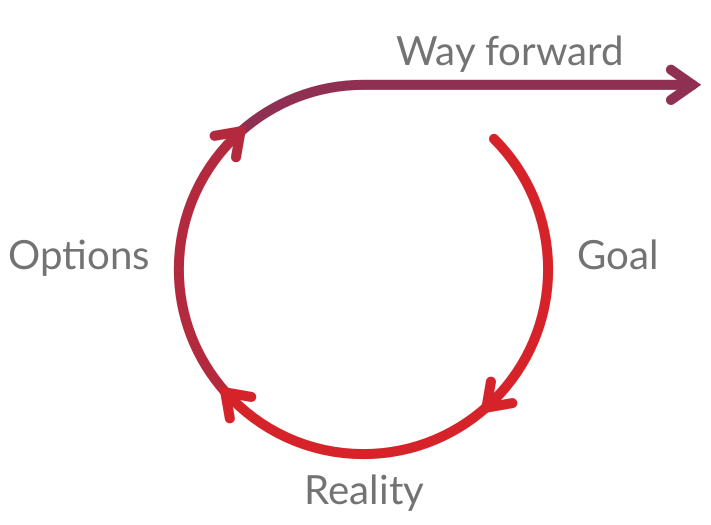

1. The GROW Model

Source: Compassiontolead.net

Perhaps the most well-known coaching framework, Sir John Whitmore’s GROW Model takes a four-step approach to develop the coach-client relationship. It’s an acronym for:

- Goal: Determining the coachee’s ultimate aims;

- Reality: Exploring their existing “reality,” or contexts, before pursuing any action.

- Options/Opportunities: Investigating what options exist for them; and

- Way Forward/What’s Next: Determining on an action(s) they’ll be pursuing.

For example:

Bob aims to progress from being a snowboarder to becoming a snowboard instructor (Goal). He and his life coach talk about the current realities of his situation – he doesn’t have money to train as an instructor, and he has never taught before.

Together, they investigate how he could make more money for the training and also gain teaching experience (Options). Bob looks further into training institutions at home, and his coach suggests some jobs he might try out to earn cash and get some teaching experience.

We can see right away that the skills required by Bob’s coach include things like active listening, asking the right questions, and strength-spotting, among others. A common critique of the GROW model, on the other hand, is that it doesn’t sufficiently consider a client’s past – this has led to variants of the original such as the REGROW framework (Grant, 2011).

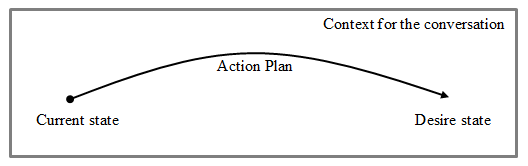

2. The FUEL Model

Source: Zenger and Stinnett (2010)

Developed by Zenger and Stinnett (2010), the FUEL model provides a set of coaching pathways for guiding the process. Like the GROW model, it has four key aspects (Clemmer Group, 2015):

- Framing the coaching conversation – outlining the aim of the coaching and the process, which includes discussions around evaluation, feedback, and so forth;

- Understanding the client’s current state – concerning their perspectives, beliefs, and any thought patterns at play;

- Exploring their desired state – helping the client envision their success and understanding that it will probably involve change; and

- Laying out a plan of action for reaching that state.

As with the GROW framework – as with all frameworks, to be fair – a successful outcome relies heavily on the individual coach’s skills and their ability to build a trusting relationship with the client. Zenger and Stinnett also argue that it is more flexible than GROW, offering more potential workplace applications and a greater likelihood of staying on track than the former, thanks to the Understanding stage (Clemmer Group, 2015).

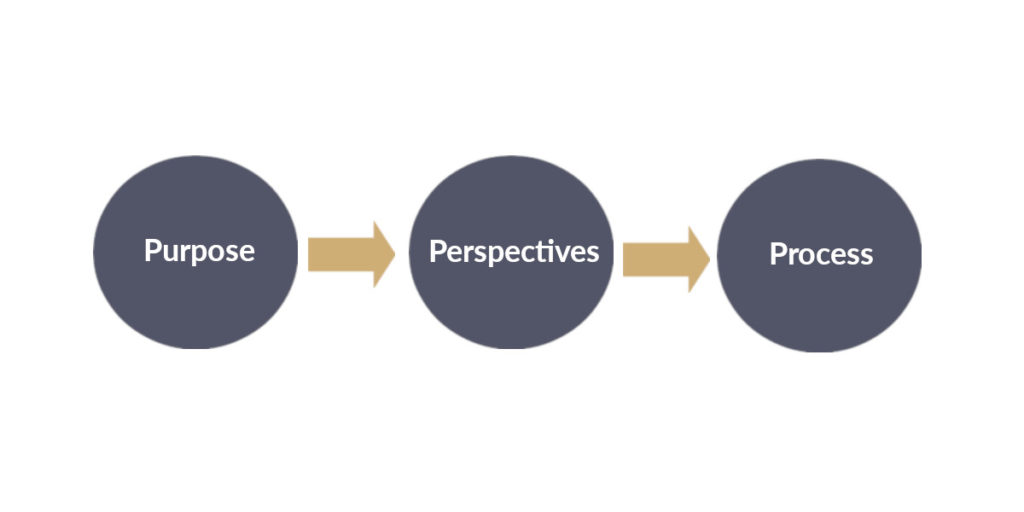

3. Purpose, Perspectives, Process

Source: Adapted from Stout-Rostron (2018)

This framework was developed by Lane and Corrie (2006) and encompass three steps, as the name suggests (Stout-Rostron, 2018):

- Purpose – Which covers the rationale for the coaching relationship and the coachee’s goals: “Where and why”;

- Perspectives – What perspectives are going to shape the process? What backgrounds, values, interpretations, assumptions, and so forth will the coach and client bring to the table?

- Process – How will we work together to get there?

This model helps the coach understand a coachee’s requirements, establish rapport, understand their desired outcomes, and begin a process together from the same place. Stout-Rostron’s (2018) book gives a pretty nice first-hand description from a coach who has enacted this framework.

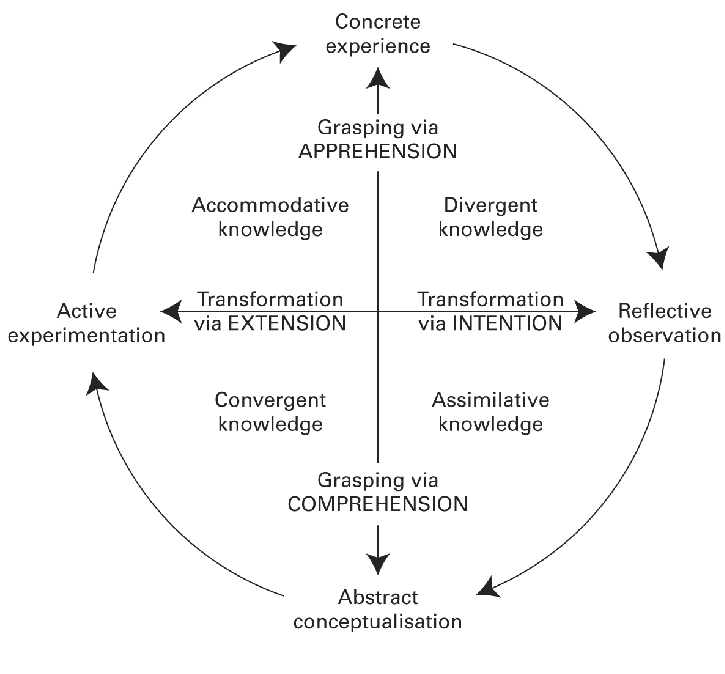

4. Kolb’s Experiential Learning Model

Source: Ord & Leather (2011)

Kolb’s work on learning has been highly influential in business settings, but it has far broader implications and can be valuable in life coaching, too. The premise of Kolb’s (1984) Experiential Learning Model is that a coach or mentor can transform a client’s experiences into usable knowledge in a way that we can’t always do by ourselves.

You, me – all of us – go through a consistent cycle of continued learning through various stages, argues Kolb:

- Concrete experiences – trying to ride a bike, for instance, where we feel and experience;

- Reflective observation on them – e.g., “Every time I wobbled, it’s because I was leaning to one side”;

- Abstract conceptualization – “I wonder how I’d go about not leaning to one side”; and

- Active experimentation – going out and doing, trying things out, or practicing.

Coaching using this model is focused on integrating the stages where the connections might not otherwise be made (Griffiths, 2005). If we pop back to Bob the snowboarder, for instance, he might never have realized that working as a tutor or teaching assistant would give him some concrete experience to become a snowboarding instructor.

Coaching Techniques for the Workplace

To recap, important workplace coaching techniques include:

- Building trust;

- Active listening;

- Asking open-ended questions;

- Effective goal-setting;

- Encouraging an outcome focus;

- Fostering engagement with goals;

- Providing support on the development journey;

- Giving constructive feedback;

- Strengths-spotting;

- Making resources available where required;

- Motivating employees; and

- Balancing extrinsic and intrinsic rewards.

Outside of the coaching sessions themselves, leaders and managers need to consider how to build a healthy workplace culture that is conducive to learning and professional development. This is linked intrinsically with psychological safety – the idea that mistakes are viewed as normal, questions are encouraged, and workers feel comfortable asking for feedback (Lipshitz et al., 2002).

Our toolkit is full of more useful exercises and assessments that leaders and managers can use to develop these practical skills, such as a 360-degree feedback Strengths Scoring Sheet and our Work and Well-being Survey.

How to Best Improve Your Coaching Skills?

Experience is usually the best way to improve your coaching skills, but as Kolb would argue, it’s possible to speed up your progress by consciously practicing relevant techniques. As with any learning process, enhanced performance starts with awareness – what do you view as your strengths? What are the points that you’d love to develop?

Based on the skills and techniques we’ve looked at in this resource, you may want to:

- Research and understand the psychological importance of the skills themselves – e.g., why do values matter? How can we help our clients set meaningful life goals, the right way? How can I encourage them to own their development goals and take accountability for them?

- Work actively on your EQ skills with Emotional Intelligence Training;

- Widen your palette of communication skills – this will help you take an adaptive approach to build coaching relationships, and it will help you move forward while maintaining a solution-focus;

- Learn more about the theory behind different coaching models and how to implement them – what are the strengths of each? How do they fit in with your current approach, your typical clients?

Studies of coaching skills interventions have also used feedback techniques and EQ training to help leaders improve their approach. This research by Grant (2007) saw managers:

- Undergoing an intensive face-to-face course on coaching skills;

- Practicing their skills in the workplace;

- Writing their experiences up as case studies; and

- Using the case studies to make analytical reflections on their performance.

In these cases, coaching leaders also had others observe their coaching sessions to provide structured feedback. All in all, the results suggested that short, regular training was more effective than longer, one-off training for coaches who wanted to improve their skills – provided the training involved feedback.

Notes on Group Coaching

Team Coaching in the Workplace

Where groups take part in development sequences together in the workplace, it’s usually considered team coaching:

…direct interaction with a team intended to help members make coordinated and task-appropriate use of their collective resources in accomplishing the team’s work.

The coaching process itself will involve wholly different dynamics from the one-on-one coaching we’ve discussed so far, as well as distinct emphases and collective rather than individual goals.

It’s fair to say that a lot of the time in group working situations, an external facilitator may be involved, or the team leader may themselves step back into a facilitator role – at least for some of the sequence.

Team members may even coach each other, depending on the nature of the sequence or intervention, so a whole host of other skills come into play on a leader’s part. Very briefly, these can include, but aren’t limited to (Marks et al., 2001; Hackman & Wageman, 2005):

- Collective goal specification

- Team coordination and monitoring;

- Resource management; and

- Conflict management.

Group Life Coaching

On top of the interpersonal considerations just listed, group life coaching involves a host of logistical skills that wouldn’t ordinarily fall under a life coach’s expertise. Outside of organizational contexts, group life coaches don’t have the convenience of ready-made teams on hand.

Scaling up processes which have been initially designed for one-on-one clients takes effort and hard work, but with a ready market for group life coaching, it’s possible.

Our Positive Psychology Toolkit has group exercises, activities, and interventions that are designed specifically for groups.

7 Best Books to Read on Developing Coaching Skills

Here are some excellent books for coaches, several of which are focused on asking the right questions. We’ve also included a read or two about coaching with mindfulness, using emotional intelligence in coaching, and other skills that could help you develop your unique approach holistically.

- The Coaching Habit: Say Less, Ask More & Change the Way You Lead Forever by Michael Bungay Stanier (Amazon)

- Effective Coaching: Lessons from the Coach’s Coach by Myles Dowley (Amazon)

- Change Your Questions, Change Your Life: 12 Powerful Tools for Leadership, Coaching, and Life by Marilee Adams (Amazon)

- Mindful Coaching: How Mindfulness Can Transform Coaching Practice by Liz Hall (Amazon)

- Emotional Intelligence Coaching: Improving Performance for Leaders, Coaches and the Individual by Steven Neale, Lisa Spencer-Arnell, and Liz Wilson (Amazon)

- Simple Habits for Complex Times: Powerful Practices for Leaders by Jennifer Garvey Berger and Keith Johnston (Amazon)

- Trillion Dollar Coach: The Leadership Playbook of Silicon Valley’s Bill Campbell by Eric Schmidt, Jonathan Rosenberg, and Alan Eagle (Amazon)

Another useful way to enhance your coaching skills would be to target the specific skills that you feel are most relevant to take your practice to the next level. This article about the Best Books on Emotional Intelligence might be useful, while we also have a more comprehensive list of 20 Top Life-coaching Books.

A Take Home Message

Nobody is born with a full set of coaching skills, but you don’t need a million years of experience to become an effective coach. We’ve broken down a whole bunch of broader concepts here into smaller ones, but it’s not difficult to see that a lot of it comes down to a few key things.

Coaches rely on emotional intelligence to communicate with their clients, to understand their perspectives, give feedback, and more. They use cognitive intelligence to take key concepts and apply them into practice, and all coaches use elements of positive psychology to motivate others.

At the same time, an effective coaching process or sequence will be firmly based on personal values, and ideally, it will develop one’s strengths to achieve the client’s desired goal.

Whether you want to become a snowboarding instructor like Bob, or you want to coach your project team to success, these skills will likely make a substantial positive difference along the way.

This article originally appeared on Positive Psychology.